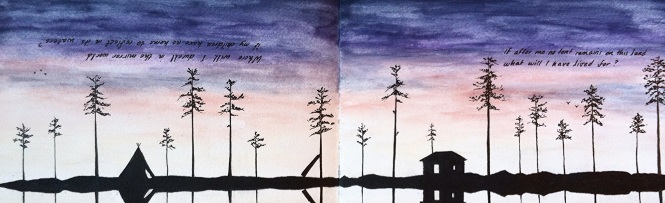

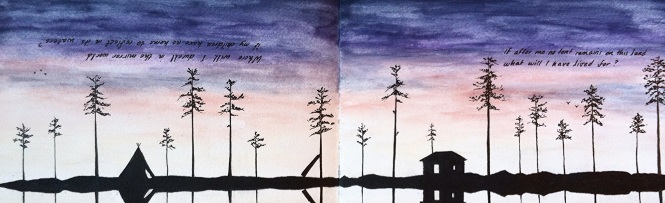

“If no tent remains on this land after I am gone, what will I have lived for?”

-Khanty elder as quoted by Yuri Vela in “The Last Monologue”

Khanty Identity in 21st Century Russia

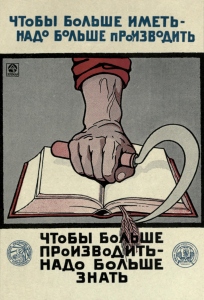

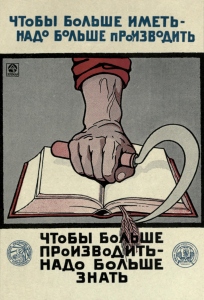

Understanding the meaning of our lives is a universal quest. While there are those of us who choose to withdraw from ourselves and society, most of us spend the majority of our time on this earth trying to leave some mark, be it altruistic, artistic, scholarly, monetary, or physical. In order to promote the continued functioning of our sociopolitical systems, most societies promote productivity among its citizens, encouraging us to work hard and reap the reward of a good life. Our jobs, our wealth, our contribution to collective knowledge bring purpose to our lives, we are told from childhood. This is not a recent development, nor is it confined to Fordist and post-Fordist societies. The Soviets ingrained the mantra “To have more, we must produce more,” into Russians’ psyches with such vigor that people still believe they must live and work in the same paradigm today. The meaning of life for most Russians is in their ability to have a family, an apartment, and a car; to exist passively in the nebulous, post-Soviet urban landscape.

Understanding the meaning of our lives is a universal quest. While there are those of us who choose to withdraw from ourselves and society, most of us spend the majority of our time on this earth trying to leave some mark, be it altruistic, artistic, scholarly, monetary, or physical. In order to promote the continued functioning of our sociopolitical systems, most societies promote productivity among its citizens, encouraging us to work hard and reap the reward of a good life. Our jobs, our wealth, our contribution to collective knowledge bring purpose to our lives, we are told from childhood. This is not a recent development, nor is it confined to Fordist and post-Fordist societies. The Soviets ingrained the mantra “To have more, we must produce more,” into Russians’ psyches with such vigor that people still believe they must live and work in the same paradigm today. The meaning of life for most Russians is in their ability to have a family, an apartment, and a car; to exist passively in the nebulous, post-Soviet urban landscape.

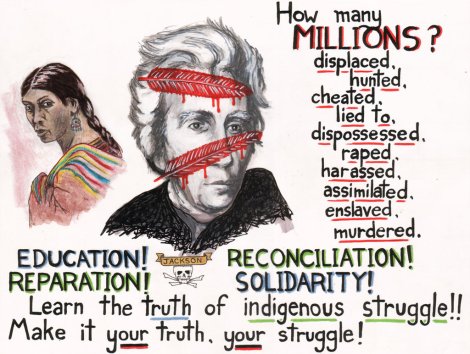

For the Khanty, one of Russia’s 23 indigenous tribes, life’s meaning is not found in a brutalist apartment building of a city. Their purpose in life has always been tied to the taiga, to being stewards of its forests, rivers, and swamps. Despite 3,000 years of invasions, persecution, forced integration, and disenfranchisement, the Khanty have held onto this purpose as it is what has always defined their identity. But after surviving the Soviet regime, in which they were forced to abandon their homes and value system in favor of the new socialist order, many Khanty are now wondering how they can regain their life’s meaning in a land that is quickly slipping from their grip.

Witnessing Life in the Taiga

The sad truth is that today, a Khanty man has only 50 years on average to ensure the continuation of his land and legacy. Shockingly, only 70% of Khanty live beyond age 60, ten years below the national average. When I asked a friend in St. Petersburg why people in Russia’s rural communities die so young, she told me it was because of the stress of living through the Soviet Union. Perhaps this is true, but the Soviet Union collapsed 24 years ago and these statistics are not changing.

Sure, someone far removed from the reality of rural life could say, “They die young because they’re all alcoholics and smokers,” as they themselves sit in their comfortable flat with a cigarette in one hand and a bottle in another (true scenario). But let’s allow ourselves to imagine that the Khanty’s abhorrently short life expectancy may in fact be due to a combination of Soviet and post-Soviet environmental conditions; conditions the state, bootlegging corporations, and they themselves have shaped with troubling consequences.

Western researchers and activists have written several compelling books and articles on the Khanty and their struggle for survival in the face of the oil and gas complex. This is how I first came to learn about Sasha Aipin. 350’s Western Caucus Coordinator, Yulia Makliuk, published a post highlighting the resilience of the Aipin clan in the face of the oil companies illegally drilling on their land. Yulia gave me Sasha’s contact and after 13 months of Google-translated email exchanges, I found myself sitting in the log cabin of his summer settlement, surrounded by his male kin, eating reindeer stew and salted fish.

Western researchers and activists have written several compelling books and articles on the Khanty and their struggle for survival in the face of the oil and gas complex. This is how I first came to learn about Sasha Aipin. 350’s Western Caucus Coordinator, Yulia Makliuk, published a post highlighting the resilience of the Aipin clan in the face of the oil companies illegally drilling on their land. Yulia gave me Sasha’s contact and after 13 months of Google-translated email exchanges, I found myself sitting in the log cabin of his summer settlement, surrounded by his male kin, eating reindeer stew and salted fish.

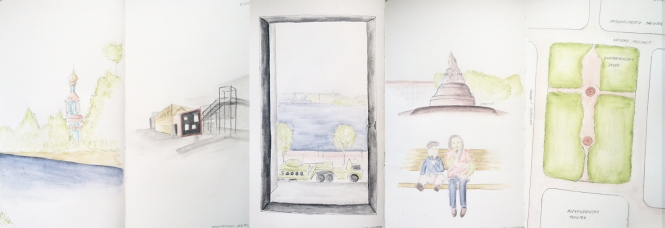

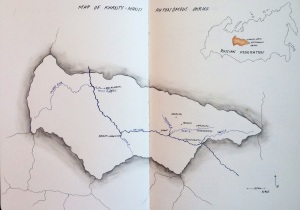

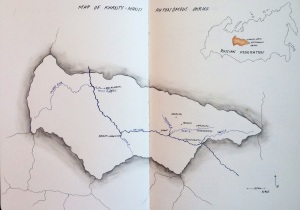

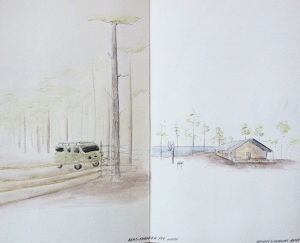

I spent the past month in this way, exploring the homes (in cities, villages, and settlements) of Khanty families along the Agan and Kazim, two rivers that feed the majestic Ob-Irtish, the world’s third-largest river system.

While most of the articles about the Khanty concentrate on the injustices done to them in the last 100 years, these landscapes told of a much more ancient struggle, one that goes back over 3,000 years and relates as much to the Khanty’s livelihood security as it does to their identity as a people.

This post cannot possibly do justice to the last month’s worth of experiences, new friends, and research I gathered. However, I hope that in reading this you will at least glimpse the reality for a people whose existence in this environment from the very start has been a struggle. And I hope you will see how our world’s insatiable appetite for fossil fuels and the corruption of this government and the corporations invested in it impact not only Khanty’s life expectancy but life meaning, as well.

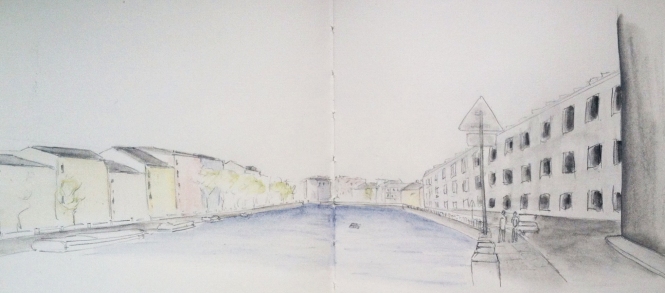

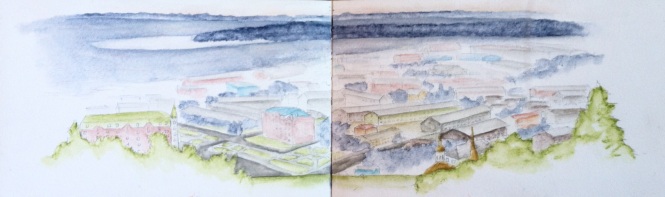

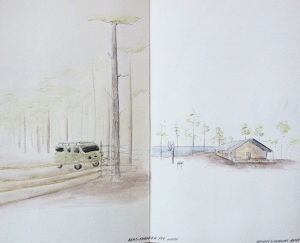

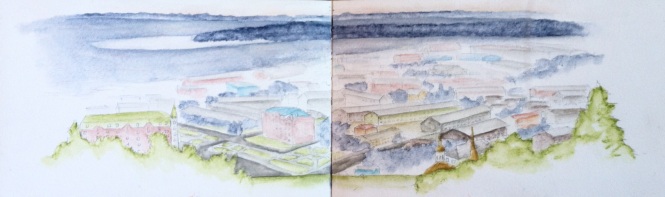

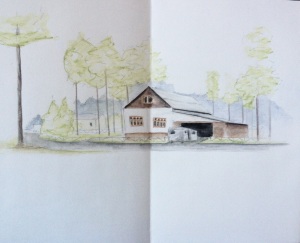

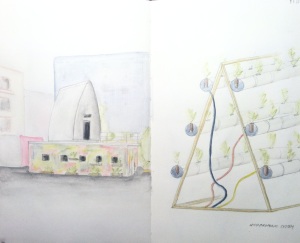

Khanty-Mansiysk, Ugra’s capitol city

Taming the Taiga

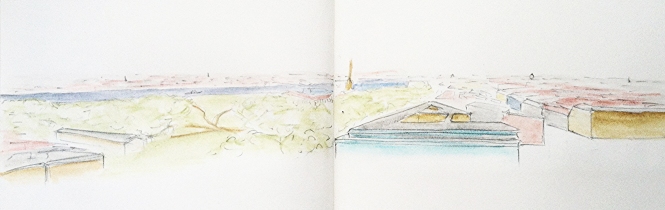

I assumed that after ten months in equatorial climates, a month in Russia’s cool northern forests would be a nice break from extreme conditions. On the contrary, these were the harshest environmental conditions I have faced thus far: extremes of hot and cold, white nights, and worst of all mosquitoes. When I visualized Borneo, the Amazon, and the Omo Valley, mosquitoes were a big part of the picture. But the numbers in those environments were nothing compared to what you find in the taiga. The Ob-Irtysh River system drains the west Siberian basin, defined on the east by the Yenesi River highlands, the south by the Altai steppes, and the west by the Ural Mountains. In May, several meters of ice and snow break apart and flood the valley, submerging 1.6 million km2 (the size of Alaska) of peat-swamps and conifer forests under water. Not only does this make building difficult and maintenance costly, it provides the perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes and disease-bearing ticks.

I assumed that after ten months in equatorial climates, a month in Russia’s cool northern forests would be a nice break from extreme conditions. On the contrary, these were the harshest environmental conditions I have faced thus far: extremes of hot and cold, white nights, and worst of all mosquitoes. When I visualized Borneo, the Amazon, and the Omo Valley, mosquitoes were a big part of the picture. But the numbers in those environments were nothing compared to what you find in the taiga. The Ob-Irtysh River system drains the west Siberian basin, defined on the east by the Yenesi River highlands, the south by the Altai steppes, and the west by the Ural Mountains. In May, several meters of ice and snow break apart and flood the valley, submerging 1.6 million km2 (the size of Alaska) of peat-swamps and conifer forests under water. Not only does this make building difficult and maintenance costly, it provides the perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes and disease-bearing ticks.

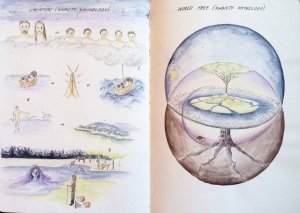

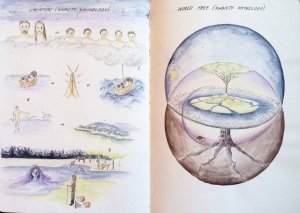

Sub-zero winters and mosquito-ridden summers coupled with poor soil quality may not sound like an ideal environment for a group of subsistence agriculturalists from the Ural steppes. But in 2,000 B.C., when Central Asian tribes were expanding north, the Khanty had little choice but to settle the lower-Ob. For several hundred years they subsisted off of fish, game, and berries. They built large communal subterranean homes along the tributaries of the Ob and Irkutsk. As the world south of them became more connected with the Silk Road, trade of furs for tools, vessels, fabrics, and beads gained importance.

Sub-zero winters and mosquito-ridden summers coupled with poor soil quality may not sound like an ideal environment for a group of subsistence agriculturalists from the Ural steppes. But in 2,000 B.C., when Central Asian tribes were expanding north, the Khanty had little choice but to settle the lower-Ob. For several hundred years they subsisted off of fish, game, and berries. They built large communal subterranean homes along the tributaries of the Ob and Irkutsk. As the world south of them became more connected with the Silk Road, trade of furs for tools, vessels, fabrics, and beads gained importance.

Invading Nomads (800-1600 A.D.)

Beginning in 800 A.D., a series of nomadic peoples swept across south Siberia, most notably the Tatars. For several hundred years, the Tatars controlled the major ports along the rivers and imposed a tax (of furs) on the Khanty. Warfare over the control of the fur trade led to the rise of a stratified society, led by chieftains. Simultaneously their living systems formalized into fortified villages along main waterways. There was some cultural exchange and intermarriage between the Khanty and Tatars but the Khanty continued to adhere to their traditional modes of livelihood and their cultural identity stayed largely intact.

Colonization by the Tsars and Church (1600-1917 A.D.)

The early 1600s marked the start of 300 years of tsarist rule. The Russians spread east quickly, establishing administrative centers and using both physical violence and religious proselytizing to undermine the Khanty chieftains and shamans. Following the demise of their caste system, Khanty scattered from fortified towns to family settlements. Greater Russian access to the hinterland put pressure on game and fisheries. But despite the occupation of their land by the Russians, the Khanty maintained their identity as a people and stewards of the taiga.

They began to define borders around family hunting grounds and many north of the Ob adopted reindeer herding as a means of guaranteeing year-round meat availability for consumption and trade. As caretakers of the deer, they had to ensure their access to fresh “pastures” (coniferous forests with thick floors of white lichen). Herders adopted a nomadic lifestyle to follow the deer to seasonally-appropriate pastures. This expanded their conceptualization of their “home territory”.

Surviving the Soviets

During the Civil War, when tsarist and Soviet troops swept across the taiga killing anyone who might be their opposition (i.e. everyone), many Khanty retreated upriver. Beginning in the 1930s, however, Soviet collectivization forced most Khanty into villages and working cooperatives. Ugra (officially Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug today) was rich in natural resources (namely timber, fish, and fur). The government therefore prioritized the establishment of working cooperatives here in order to fill the deficit of these resources in the west. Clans with reindeer were required to hand them over to the state, then form cooperatives to herd them collectively. Clans south of the Ob whose livelihoods depended on fishing had to turn in their catch; those who were caught fishing and selling privately were held in contempt of the state and punished.

Collectivization was intended to break individual connection to property and capital by reorganizing labor on a communal basis, centrally administering production, and distributing resources “equally” across all of Russia. But this totalitarian methodology did not have the desired effect. Working cooperatives (based on clan divisions) were already a part of many Khanty communities so peoples’ sense of personal entitlement was not destroyed in the same way it was with neighboring Russian communities. Several Khanty villages, including Kazim and Varyogan where I stayed, found means of both active (in the case of the 193X Kazim Revolt) and passive resistance to collectivization. The Aipin clan, for example, kept settlements along the Agan and Enel Rivers while simultaneously living in Varyogan and sending their children to school at the mandatory Internat boarding schools.

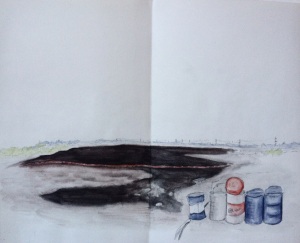

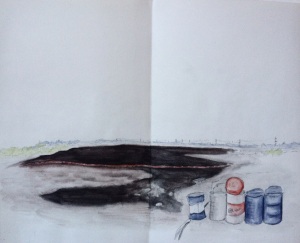

Things changed for the Khanty in 1960s with the discovery of oil. The state began to drill immoderately, with no regard to environmental preservation or conservation of the Khanty’s sacred cultural sites. Large towns sprang up near the oil fields, notably Beloyarski near Kazim and Novoagansk near Varyogan. The 1970s marked the forced relocation of families from their traditional hunting and herding territories to make room for oil and gas development. As towns grew, roads constructed, and game and fish dwindled (from over-consumption by incoming Russians and habitat loss), many Khanty chose to move into town to access services and employment. According to Fondahl, by the 1980s, planned burning and oil spills had already destroyed 220,000 km2 (the size of the UK) of reindeer pasture and hunting grounds.

By the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, most Khanty had homes in town, owned cars and snowmobiles, and earned wages. But while Soviet development may have created dependency on the cash economy and increased rates of alcoholism and crime, it had not erased the Khanty’s identification with their land and culture.

Environmental Injustice in the 21st Century

Post-Soviet privatization led to the dissolution of the state oil monopoly and bootlegging oil companies took over production. Legislation was introduced in 1993, which allowed the Khanty to redraw their customary land boundaries prior to the Soviet Union. However, land rights have been poorly implemented and protected because government officials have vested interests in companies eager to drill on Khanty land. Companies are supposed to obtain lease and compensation agreements from the Khanty before drilling or building related infrastructure, but these are often falsified, signatures are coerced, and drilling continues without the Khanty’s knowledge or consent. Many Khanty complain that even when they do give conditional consent, companies do not fulfill their promises for compensation (read Chapter 7 of Andrew Wiget’s Khanty, People of the Taiga to learn more).

Post-Soviet privatization led to the dissolution of the state oil monopoly and bootlegging oil companies took over production. Legislation was introduced in 1993, which allowed the Khanty to redraw their customary land boundaries prior to the Soviet Union. However, land rights have been poorly implemented and protected because government officials have vested interests in companies eager to drill on Khanty land. Companies are supposed to obtain lease and compensation agreements from the Khanty before drilling or building related infrastructure, but these are often falsified, signatures are coerced, and drilling continues without the Khanty’s knowledge or consent. Many Khanty complain that even when they do give conditional consent, companies do not fulfill their promises for compensation (read Chapter 7 of Andrew Wiget’s Khanty, People of the Taiga to learn more).

Without protection or effective political voice, many Khanty who choose to stay on their lands are literally witnessing their demise. This report for Greenpeace includes a fairly comprehensive list of environmental disasters in Ugra associated with oil pollution. I saw my own fair share of spills, careless burning and clearing of sites for pipelines and oil fields, polluted waters, and the long-term impact this activity has had on fisheries and forest health.

I first stayed with a family near Kogalym who had given permission for a company to drill adjacent to their property line (100 meters from their home). In exchange, both parents have jobs working for the company, receive pellets for their reindeer, and get electricity wired to them from the station. While it is trivial price for the company to pay for the huge profits it is raking in off of this land, the cost for this family is still unfolding. Runoff from leaky pipes has wound up in their drinking water supply, their reindeer are now isolated from their traditional feeding grounds, and the family is dependent on the company for their livelihood generation. Who knows what might happen to them in the future.

I first stayed with a family near Kogalym who had given permission for a company to drill adjacent to their property line (100 meters from their home). In exchange, both parents have jobs working for the company, receive pellets for their reindeer, and get electricity wired to them from the station. While it is trivial price for the company to pay for the huge profits it is raking in off of this land, the cost for this family is still unfolding. Runoff from leaky pipes has wound up in their drinking water supply, their reindeer are now isolated from their traditional feeding grounds, and the family is dependent on the company for their livelihood generation. Who knows what might happen to them in the future.

After Kogalym, I took a boat up the Agan River to Sasha Aipin’s summer settlement. As Yulia details in her article, Sasha’s family has been one of the few to actively fight the invasion of companies. As a family that has one foot in each world – splitting their time between Varyogan and Novoagansk, where the women work and children attend school, and the settlements, where the men tend to their reindeer, hunt and fish – the Aipins understand the importance of safeguarding the environment from reckless profiteers, both for the conservation of their deer’s habitats and for their own health and longevity. The Aipins were the only family I met who were relatively successfully able to balance their lives between the forest and the town.

After Kogalym, I took a boat up the Agan River to Sasha Aipin’s summer settlement. As Yulia details in her article, Sasha’s family has been one of the few to actively fight the invasion of companies. As a family that has one foot in each world – splitting their time between Varyogan and Novoagansk, where the women work and children attend school, and the settlements, where the men tend to their reindeer, hunt and fish – the Aipins understand the importance of safeguarding the environment from reckless profiteers, both for the conservation of their deer’s habitats and for their own health and longevity. The Aipins were the only family I met who were relatively successfully able to balance their lives between the forest and the town.

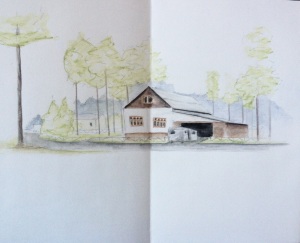

In the north, 30 km east of Beloyarski is Kazim, a traditional Khanty village famous for its resistance to Soviet collectivization in the 1930s. There, I spent a week with a family who has nearly lost touch with their forest and therefore distanced (but not removed) from the impact of oil. In Kazim, less than 15% of families still herd reindeer. The rest commute to Beloyarski daily to work in the service, cultural, or oil sector. While they still celebrate the aesthetic elements of their culture – including clothing, basket-making, stories, and traditional music – I wondered how their children will be able to identify as Khanty if they never know the forest or its forms of livelihood generation.

In the north, 30 km east of Beloyarski is Kazim, a traditional Khanty village famous for its resistance to Soviet collectivization in the 1930s. There, I spent a week with a family who has nearly lost touch with their forest and therefore distanced (but not removed) from the impact of oil. In Kazim, less than 15% of families still herd reindeer. The rest commute to Beloyarski daily to work in the service, cultural, or oil sector. While they still celebrate the aesthetic elements of their culture – including clothing, basket-making, stories, and traditional music – I wondered how their children will be able to identify as Khanty if they never know the forest or its forms of livelihood generation.

What Now?

If no tent remains on this land after I am gone, what will I have lived for?

In his article for Cultural Survival, Wigit explains eloquently:

“(Establishing resource security and autonomy in choosing one’s own future) is obviously an enormously complex process, and perhaps nowhere more so than in Russia, where the process is constrained by the absence of a legal basis for recognizing native peoples as distinct communities with their own interests, by deeply embedded authoritarian habits, and by an economy driven by the need for hard currency derived from the export of Siberian natural resources. As Russia moves toward developing regulations that balance national interests with private development, what is needed is an effective, integrated process of environmental, social, and cultural impact assessment.”

Action needs to be taken on all levels if the Khanty are to regain their livelihood security and preserve their identities, which are tied to the forests. Decreasing consumption of fossil fuels on an international level, calling out the international human rights violations being undermined, lobbying federal and oblast administrations to strengthen and uphold the legislation they create, and grassroots action by Khanty communities themselves are all critical.

Dependency is the biggest threat I see to resisting the injustices happening to them. Dependency causes fragmentation, blindness, apathy, and loss of identity. But there is power both in the telling of this struggle and the retelling of the Khanty’s past. I got to spend my last week in Ugra at a Khanty children’s summer camp upriver from Kazim. There, thirty children gathered to learn from elders about their Khanty roots. Separated from the televisions and smartphones that acculturate them at home, they spent the week sleeping in a chum (a traditional tipi nomadic herders once used), making baskets and jewelry, playing games, and performing Khanty theater and dance. Witnessing these children’s excitement was an inspiring way to end my time in Ugra. It shows that their identity and life purpose might be able to encompass both worlds: that of the forest, and that of our inescapable mainstream society. And with this evolved identity can come unity, resilience, and hopefully justice: a damn good thing to have lived for.

Further Reading

Dean, Bartholomew, and Jerome M. Levi. At the risk of being heard: identity, indigenous rights, and postcolonial states. University of Michigan Press, 2003.

Fondahl, Gail, Viktoriya Filippova, and Liza Mack. “Indigenous Peoples in the New Arctic.” The New Arctic. Springer International Publishing, 2015. 7-22.

Gerasimova, Elena. “Russia: Khanty take action to stop road construction through sacred site by oil company.” Reindeer Herders, April 30, 2014.

Glavatskaya, Elena. “Religious and ethnic revitalization among the Siberian Indigenous people: The Khanty case.” Senri ethnological studies (2004).

Haller, Tobias, ed. Fossil Fuels, Oil Companies, and Indigenous Peoples: Strategies of Multinational Oil Companies, States, and Ethnic Minorities: Impact on Environment, Livelihoods, and Cultural Change. Vol. 1. LIT Verlag Münster, 2007.

Ingram, Verina, and Willemse, Reimond. “West Siberia Oil Industry Environmental and Social Profile.” Report for Greenpeace, 2001.

Leonard, William R (April 2002). “Declining growth status of indigenous Siberian children in post-Soviet Russia”. Human Biology. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

Makliuk, Yulia. “Will the Khanty Save Russia?” 350.org, 2013.

Pentikainen, Juha. “Khanty shamanism today: Reindeer sacrifice and its mythological background.” Shamanism and Northern Ecology 36 (1996): 153.

Ugra Investment Report, 2012.

Wiget, Andrew. “Black Snow: Oil and the Khanty of West Siberia.” Cultural Survival, 1996.

Wiget, Andrew, and Olga Balalaeva. Khanty, People of the Taiga: Surviving the 20th Century. University of Alaska Press, 2011.

Slezkine, Yuri. “The USSR as a communal apartment, or how a socialist state promoted ethnic particularism.” Slavic Review (1994): 414-452.

Sunderland, Willard. “Russians into Iakuts?” Going Native” and Problems of Russian National Identity in the Siberian North, 1870s-1914.” Slavic Review(1996): 806-825.

I assumed that after ten months in equatorial climates, a month in Russia’s cool northern forests would be a nice break from extreme conditions. On the contrary, these were the harshest environmental conditions I have faced thus far: extremes of hot and cold, white nights, and worst of all mosquitoes. When I visualized Borneo, the Amazon, and the Omo Valley, mosquitoes were a big part of the picture. But the numbers in those environments were nothing compared to what you find in the taiga. The Ob-Irtysh River system drains the west Siberian basin, defined on the east by the Yenesi River highlands, the south by the Altai steppes, and the west by the Ural Mountains. In May, several meters of ice and snow break apart and flood the valley, submerging 1.6 million km2 (the size of Alaska) of peat-swamps and conifer forests under water. Not only does this make building difficult and maintenance costly, it provides the perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes and disease-bearing ticks.

I assumed that after ten months in equatorial climates, a month in Russia’s cool northern forests would be a nice break from extreme conditions. On the contrary, these were the harshest environmental conditions I have faced thus far: extremes of hot and cold, white nights, and worst of all mosquitoes. When I visualized Borneo, the Amazon, and the Omo Valley, mosquitoes were a big part of the picture. But the numbers in those environments were nothing compared to what you find in the taiga. The Ob-Irtysh River system drains the west Siberian basin, defined on the east by the Yenesi River highlands, the south by the Altai steppes, and the west by the Ural Mountains. In May, several meters of ice and snow break apart and flood the valley, submerging 1.6 million km2 (the size of Alaska) of peat-swamps and conifer forests under water. Not only does this make building difficult and maintenance costly, it provides the perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes and disease-bearing ticks. Sub-zero winters and mosquito-ridden summers coupled with poor soil quality may not sound like an ideal environment for a group of subsistence agriculturalists from the Ural steppes. But in 2,000 B.C., when Central Asian tribes were expanding north, the Khanty had little choice but to settle the lower-Ob. For several hundred years they subsisted off of fish, game, and berries. They built large communal subterranean homes along the tributaries of the Ob and Irkutsk. As the world south of them became more connected with the Silk Road, trade of furs for tools, vessels, fabrics, and beads gained importance.

Sub-zero winters and mosquito-ridden summers coupled with poor soil quality may not sound like an ideal environment for a group of subsistence agriculturalists from the Ural steppes. But in 2,000 B.C., when Central Asian tribes were expanding north, the Khanty had little choice but to settle the lower-Ob. For several hundred years they subsisted off of fish, game, and berries. They built large communal subterranean homes along the tributaries of the Ob and Irkutsk. As the world south of them became more connected with the Silk Road, trade of furs for tools, vessels, fabrics, and beads gained importance.

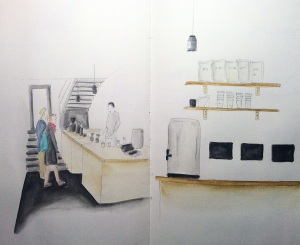

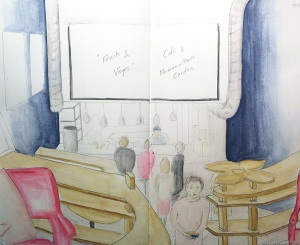

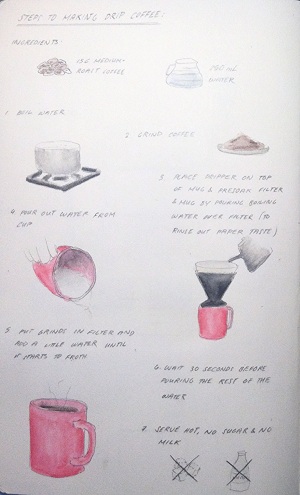

When I asked Anton to describe his business model, he admitted honestly that he doesn’t have one. “I like serving cheap food. It makes me happy to see people well-fed and unstressed about money,” he explained. This plan hasn’t always worked out for him. He had to borrow a lot of money from friends at the start of the project, which he has only now started to pay back. He also had to close for a couple of months this spring because he could not afford the rent. But things are looking up now and Anton is well on his way to achieving an “accidental” sustainable business model.

When I asked Anton to describe his business model, he admitted honestly that he doesn’t have one. “I like serving cheap food. It makes me happy to see people well-fed and unstressed about money,” he explained. This plan hasn’t always worked out for him. He had to borrow a lot of money from friends at the start of the project, which he has only now started to pay back. He also had to close for a couple of months this spring because he could not afford the rent. But things are looking up now and Anton is well on his way to achieving an “accidental” sustainable business model.

Unable to afford rent, the cooperative spent their first six months in the corner of a local bookstore. They then moved in with Anton at ArtPlay and sold coffee in Fruits and Veges for a year. Throughout this time, several members of the cooperative had no choice but to move back in with their parents. They were all supposed to be committed to this project and therefore not supplement their income with other part-time jobs. But they were barely making enough to cover their operational costs, let alone their own basic living expenses. Their approach was proving to be economically unviable and in October, they lost one of their members and decided to close for a month.

Unable to afford rent, the cooperative spent their first six months in the corner of a local bookstore. They then moved in with Anton at ArtPlay and sold coffee in Fruits and Veges for a year. Throughout this time, several members of the cooperative had no choice but to move back in with their parents. They were all supposed to be committed to this project and therefore not supplement their income with other part-time jobs. But they were barely making enough to cover their operational costs, let alone their own basic living expenses. Their approach was proving to be economically unviable and in October, they lost one of their members and decided to close for a month.